Performance work is one of those things, as they say, that ought to happen in development. You know, have a plan for it and write code that’s mindful about adding extra weight to the page.

But not everything about performance happens directly at the code level, right? I’d say many — if not most — sites and apps rely on some number of third-party scripts where we might not have any influence over the code. Analytics is a good example. Writing a hand-spun analytics tracking dashboard isn’t what my clients really want to pay me for, so I’ll drop in the ol’ Google Analytics script and maybe never think of it again.

That’s one example and a common one at that. But what’s also common is managing multiple third-party scripts on a single page. One of my clients is big into user tracking, so in addition to a script for analytics, they’re also running third-party scripts for heatmaps, cart abandonments, and personalized recommendations — typical e-commerce stuff. All of that is dumped on any given page in one fell swoop courtesy of Google Tag Manager (GTM), which allows us to deploy and run scripts without having to go through the pain of re-deploying the entire site.

As a result, adding and executing scripts is a fairly trivial task. It is so effortless, in fact, that even non-developers on the team have contributed their own fair share of scripts, many of which I have no clue what they do. The boss wants something, and it’s going to happen one way or another, and GTM facilitates that work without friction between teams.

All of this adds up to what I often hear described as a “fight for the main thread.” That’s when I started hearing more performance-related jargon, like web workers, Core Web Vitals, deferring scripts, and using pre-connect, among others. But what I’ve started learning is that these technical terms for performance make up an arsenal of tools to combat performance bottlenecks.

The real fight, it seems, is evaluating our needs as developers and stakeholders against a user’s needs, namely, the need for a fast and frictionless page load.

Fighting For The Main Thread

Contents

We’re talking about performance in the context of JavaScript, but there are lots of things that happen during a page load. The HTML is parsed. Same deal with CSS. Elements are rendered. JavaScript is loaded, and scripts are executed.

All of this happens on the main thread. I’ve heard the main thread described as a highway that gets cars from Point A to Point B; the more cars that are added to the road, the more crowded it gets and the more time it takes for cars to complete their trip. That’s accurate, I think, but we can take it a little further because this particular highway has just one lane, and it only goes in one direction. My mind thinks of San Francisco’s Lombard Street, a twisty one-way path of a tourist trap on a steep decline.

The main thread may not be that curvy, but you get the point: there’s only one way to go, and everything that enters it must go through it.

JavaScript operates in much the same way. It’s “single-threaded,” which is how we get the one-way street comparison. I like how Brian Barbour explains it:

“This means it has one call stack and one memory heap. As expected, it executes code in order and must finish executing a piece of code before moving on to the next. It’s synchronous, but at times that can be harmful. For example, if a function takes a while to execute or has to wait on something, it freezes everything up in the meantime.”

— Brian Barbour

So, there we have it: a fight for the main thread. Each resource on a page is a contender vying for a spot on the thread and wants to run first. If one contender takes its sweet time doing its job, then the contenders behind it in line just have to wait.

Monitoring The Main Thread

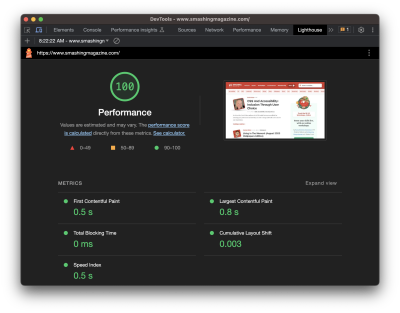

If you’re like me, I immediately reach for DevTools and open the Lighthouse tab when I need to look into a site’s performance. It covers a lot of ground, like reporting stats about a page’s load time that include Time to First Byte (TTFB), First Contentful Paint (FCP), Largest Contentful Paint (LCP), Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS), and so on.

I love this stuff! But I also am scared to death of it. I mean, this is stuff for back-end engineers, right? A measly front-end designer like me can be blissfully ignorant of all this mumbo-jumbo.

Meh, untrue. Like accessibility, performance is everyone’s job because everyone’s work contributes to it. Even the choice to use a particular CSS framework influences performance.

Total Blocking Time

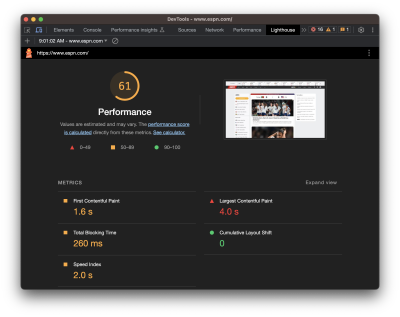

One thing I know would be more helpful than a set of Core Web Vitals scores from Lighthouse is knowing the time it takes to go from the First Contentful Paint (FCP) to the Time to Interactive (TTI), a metric known as the Total Blocking Time (TBT). You can see that Lighthouse does indeed provide that metric. Let’s look at it for a site that’s much “heavier” than Smashing Magazine.

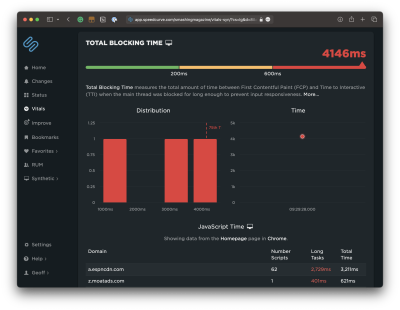

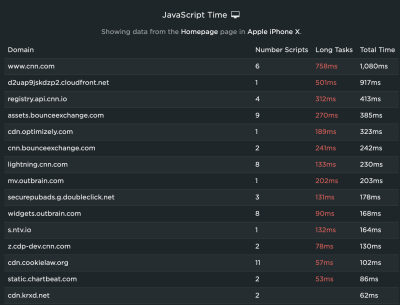

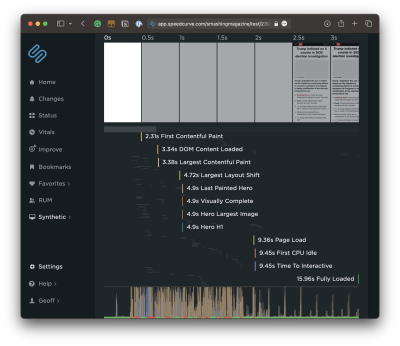

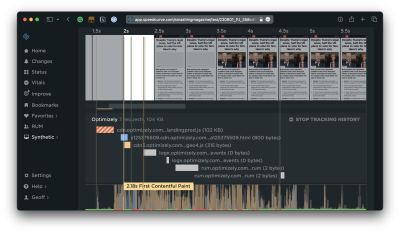

There we go. The problem with the Lighthouse report, though, is that I have no idea what is causing that TBT. We can get a better view if we run the same test in another service, like SpeedCurve, which digs deeper into the metric. We can expand the metric to glean insights into what exactly is causing traffic on the main thread.

That’s a nice big view and is a good illustration of TBT’s impact on page speed. The user is forced to wait a whopping 4.1 seconds between the time the first significant piece of content loads and the time the page becomes interactive. That’s a lifetime in web seconds, particularly considering that this test is based on a desktop experience on a high-speed connection.

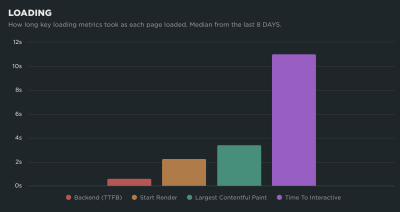

One of my favorite charts in SpeedCurve is this one showing the distribution of Core Web Vitals metrics during render. You can see the delta between contentful paints and interaction!

Spotting Long Tasks

What I really want to see is JavaScript, which takes more than 50ms to run. These are called long tasks, and they contribute the most strain on the main thread. If I scroll down further into the report, all of the long tasks are highlighted in red.

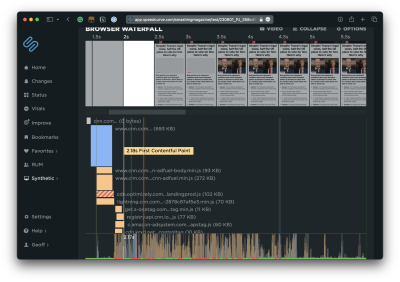

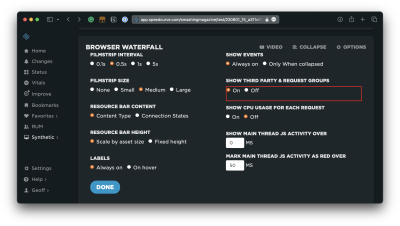

Another way I can evaluate scripts is by opening up the Waterfall View. The default view is helpful to see where a particular event happens in the timeline.

But wait! This report can be expanded to see not only what is loaded at the various points in time but whether they are blocking the thread and by how much. Most important are the assets that come before the FCP.

First & Third Party Scripts

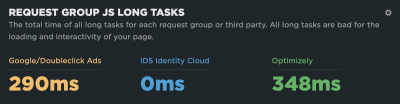

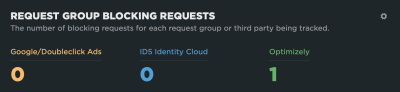

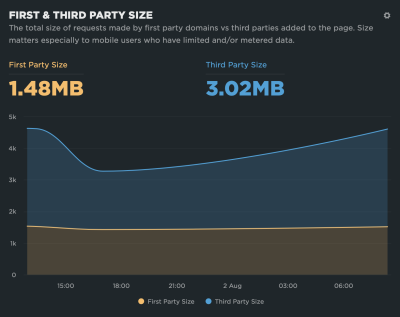

I can see right off the bat that Optimizely is serving a render-blocking script. SpeedCurve can go even deeper by distinguishing between first- and third-party scripts.

That way, I can see more detail about what’s happening on the Optimizely side of things.

Monitoring Blocking Scripts

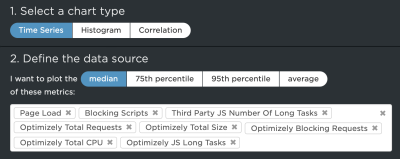

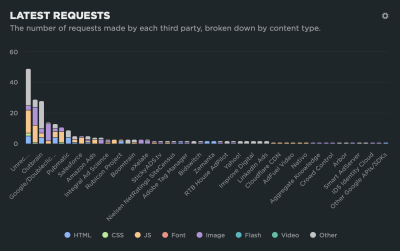

With that in place, SpeedCurve actually lets me track all the resources from a specific third-party source in a custom graph that offers me many more data points to evaluate. For example, I can dive into scripts that come from Optimizely with a set of custom filters to compare them with overall requests and sizes.

This provides a nice way to compare the impact of different third-party scripts that represent blocking and long tasks, like how much time those long tasks represent.

Or perhaps which of these sources are actually render-blocking:

These are the kinds of tools that allow us to identify bottlenecks and make a case for optimizing them or removing them altogether. SpeedCurve allows me to monitor this over time, giving me better insight into the performance of those assets.

Monitoring Interaction to Next Paint

There’s going to be a new way to gain insights into main thread traffic when Interaction to Next Paint (INP) is released as a new core vital metric in March 2024. It replaces the First Input Delay (FID) metric.

What’s so important about that? Well, FID has been used to measure load responsiveness, which is a fancy way of saying it looks at how fast the browser loads the first user interaction on the page. And by interaction, we mean some action the user takes that triggers an event, such as a click, mousedown, keydown, or pointerdown event. FID looks at the time the user sparks an interaction and how long the browser processes — or responds to — that input.

FID might easily be overlooked when trying to diagnose long tasks on the main thread because it looks at the amount of time a user spends waiting after interacting with the page rather than the time it takes to render the page itself. It can’t be replicated with lab data because it’s based on a real user interaction. That said, FID is correlated to TBT in that the higher the FID, the higher the TBT, and vice versa. So, TBT is often the go-to metric for identifying long tasks because it can be measured with lab data as well as real-user monitoring (RUM).

But FID is wrought with limitations, the most significant perhaps being that it’s only a measure of the first interaction. That’s where INP comes into play. Instead of measuring the first interaction and only the first interaction, it measures all interactions on a page. Jeremy Wagner has a more articulate explanation:

“The goal of INP is to ensure the time from when a user initiates an interaction until the next frame is painted is as short as possible for all or most interactions the user makes.”

— Jeremy Wagner

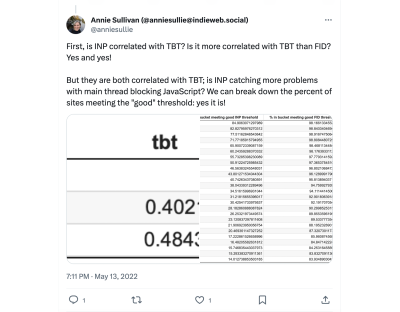

Some interactions are naturally going to take longer to respond than others. So, we might think of FID as merely a first impression of responsiveness, whereas INP is a more complete picture. And like FID, the INP score is closely correlated with TBT but even more so, as Annie Sullivan reports:

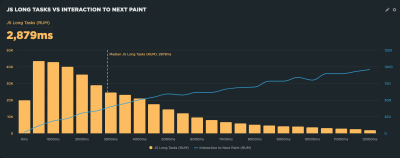

Thankfully, performance tools are already beginning to bake INP into their reports. SpeedCurve is indeed one of them, and its report shows how its RUM capabilities can be used to illustrate the correlation between INP and long tasks on the main thread. This correlation chart illustrates how INP gets worse as the total long tasks’ time increases.

What’s cool about this report is that it is always collecting data, providing a way to monitor INP and its relationship to long tasks over time.

Not All Scripts Are Created Equal

There is such a thing as a “good” script. It’s not like I’m some anti-JavaScript bloke intent on getting scripts off the web. But what constitutes a “good” one is nuanced.

Who’s It Serving?

Some scripts benefit the organization, and others benefit the user (or both). The challenge is balancing business needs with user needs.

I think web fonts are a good example that serves both needs. A font is a branding consideration as well as a design asset that can enhance the legibility of a site’s content. Something like that might make loading a font script or file worth its cost to page performance. That’s a tough one. So, rather than fully eliminating a font, maybe it can be optimized instead, perhaps by self-hosting the files rather than connecting to a third-party domain or only loading a subset of characters.

Analytics is another difficult choice. I removed analytics from my personal site long ago because I rarely, if ever, looked at them. And even if I did, the stats were more of an ego booster than insightful details that helped me improve the user experience. It’s an easy decision for me, but not so easy for a site that lives and dies by reports that are used to identify and scope improvements.

If the script is really being used to benefit the user at the end of the day, then yeah, it’s worth keeping around.

When Is It Served?

A script may very well serve a valid purpose and benefit both the organization and the end user. But does it need to load first before anything else? That’s the sort of question to ask when a script might be useful, but can certainly jump out of line to let others run first.

I think of chat widgets for customer support. Yes, having a persistent and convenient way for customers to get in touch with support is going to be important, particularly for e-commerce and SaaS-based services. But does it need to be available immediately? Probably not. You’ll probably have a greater case for getting the site to a state that the user can interact with compared to getting a third-party widget up front and center. There’s little point in rendering the widget if the rest of the site is inaccessible anyway. It is better to get things moving first by prioritizing some scripts ahead of others.

Where Is It Served From?

Just because a script comes from a third party doesn’t mean it has to be hosted by a third party. The web fonts example from earlier applies. Can the font files be self-hosted instead rather than needing to establish another outside connection? It’s worth asking. There are self-hosted alternatives to Google Analytics, after all. And even GTM can be self-hosted! That’s why grouping first and third-party scripts in SpeedCurve’s reporting is so useful: spot what is being served and where it is coming from and identify possible opportunities.

What Is It Serving?

Loading one script can bring unexpected visitors along for the ride. I think the classic case is a third-party script that loads its own assets, like a stylesheet. Even if you think you’re only loading one stylesheet &mdahs; your own — it’s very possible that a script loads additional external stylesheets, all of which need to be downloaded and rendered.

Getting JavaScript Off The Main Thread

That’s the goal! We want fewer cars on the road to alleviate traffic on the main thread. There are a bunch of technical ways to go about it. I’m not here to write up a definitive guide of technical approaches for optimizing the main thread, but there is a wealth of material on the topic.

I’ll break down several different approaches and fill them in with resources that do a great job explaining them in full.

Use Web Workers

A web worker, at its most basic, allows us to establish separate threads that handle tasks off the main thread. Web workers run parallel to the main thread. There are limitations to them, of course, most notably not having direct access to the DOM and being unable to share variables with other threads. But using them can be an effective way to re-route traffic from the main thread to other streets, so to speak.

Split JavaScript Bundles Into Individual Pieces

The basic idea is to avoid bundling JavaScript as a monolithic concatenated file in favor of “code splitting” or splitting the bundle up into separate, smaller payloads to send only the code that’s needed. This reduces the amount of JavaScript that needs to be parsed, which improves traffic along the main thread.

Async or Defer Scripts

Both are ways to load JavaScript without blocking the DOM. But they are different! Adding the async attribute to a <script> tag will load the script asynchronously, executing it as soon as it’s downloaded. That’s different from the defer attribute, which is also asynchronous but waits until the DOM is fully loaded before it executes.

Preconnect Network Connections

I guess I could have filed this with async and defer. That’s because preconnect is a value on the rel attribute that’s used on a <link> tag. It gives the browser a hint that you plan to connect to another domain. It establishes the connection as soon as possible prior to actually downloading the resource. The connection is done in advance, allowing the full script to download later.

While it sounds excellent — and it is — pre-connecting comes with an unfortunate downside in that it exposes a user’s IP address to third-party resources used on the page, which is a breach of GDPR compliance. There was a little uproar over that when it was found out that using a Google Fonts script is prone to that as well.

Non-Technical Approaches

I often think of a Yiddish proverb I first saw in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers; however, many years ago it came out:

To a worm in horseradish, the whole world is horseradish.

It’s a more pleasing and articulate version of the saying that goes, “To a carpenter, every problem looks like a nail.” So, too, it is for developers working on performance. To us, every problem is code that needs a technical solution. But there are indeed ways to reduce the amount of work happening on the main thread without having to touch code directly.

We discussed earlier that performance is not only a developer’s job; it’s everyone’s responsibility. So, think of these as strategies that encourage a “culture” of good performance in an organization.

Nuke Scripts That Lack Purpose

As I said at the start of this article, there are some scripts on the projects I work on that I have no idea what they do. It’s not because I don’t care. It’s because GTM makes it ridiculously easy to inject scripts on a page, and more than one person can access it across multiple teams.

So, maybe compile a list of all the third-party and render-blocking scripts and figure out who owns them. Is it Dave in DevOps? Marcia in Marketing? Is it someone else entirely? You gotta make friends with them. That way, there can be an honest evaluation of which scripts are actually helping and are critical to balance.

Bend Google Tag Manager To Your Will

Or any tag manager, for that matter. Tag managers have a pretty bad reputation for adding bloat to a page. It’s true; they can definitely make the page size balloon as more and more scripts are injected.

But that reputation is not totally warranted because, like most tools, you have to use them responsibly. Sure, the beauty of something like GTM is how easy it makes adding scripts to a page. That’s the “Tag” in Google Tag Manager. But the real beauty is that convenience, plus the features it provides to manage the scripts. You know, the “Manage” in Google Tag Manager. It’s spelled out right on the tin!

Wrapping Up

Phew! Performance is not exactly a straightforward science. There are objective ways to measure performance, of course, but if I’ve learned anything about it, it’s that subjectivity is a big part of the process. Different scripts are of different sizes and consist of different resources serving different needs that have different priorities for different organizations and their users.

Having access to a free reporting tool like Lighthouse in DevTools is a great start for diagnosing performance issues by identifying bottlenecks on the main thread. Even better are paid tools like SpeedCurve to dig deeper into the data for more targeted insights and to produce visual reports to help make a case for performance improvements for your team and other stakeholders.

While I wish there were some sort of silver bullet to guarantee good performance, I’ll gladly take these and similar tools as a starting point. Most important, though, is having a performance game plan that is served by the tools. And Vitaly’s front-end performance checklist is an excellent place to start.

(yk, il)